Rick: My health. I came to Casablanca for the waters.

Captain Renault: The waters? What waters? We're in the desert.

Rick: I was misinformed.

Some inaccurate information is deliberately inaccurate. A lot of COVID disinformation is this and it's worse than not accurate. It's cynical, strategic, and potentially deadly.

Second, sometimes information doesn't mean what you think it means. A lot of this is advertising, and a lot of it is deliberate sleight of hand. Colgate's famous 2007 ad "stating that 80% of dentists recommend their product" is one example. A reporter selecting the most expensive gas station on the planet to dramatically represent the price of gas is another. In some schools, a 100% graduation rate means not counting students who were "counseled into alternative settings." Charters are notorious for this.

The third kind of fake information is useless because it either is not or cannot be used. One country has launched a nuclear strike which will destroy your city in eighteen minutes. There are things you can do with your eighteen minutes, but none of them will stop the missiles.

Undoubtedly the worst, most evil type of fake information is that which is collected or generated with no intention of acting on it. Often it's generated for a reason other than the one advertised. This category was invented for state-sponsored standardized testing to which millions of k-12 students are subjected every year.

Ask most people not in education why students are tested so much, and the first thing they're likely to say is either "To find out what they know" or "They're tested how much?" A lot of people think of testing like it's the good old days, you know, when you took a final to pass your class and an SAT to get into college. Sometimes, somewhere in there was a PSAT for practice. Each one of these tests had real stakes for the students taking them, and the big standardized ones were voluntary. It was a long time ago, but I think I recall taking my SAT on a Saturday. And I had to pay for it.

That is no longer the testing environment in which we live. There are still final exams and final projects, and students usually feel connected to them because they are based on the work they've been doing in class and because the results will be reflected in their final grade.

In my school, the district required that we turn over school days and school staff to the administration of both the SAT, which was paid for by the district, and the PSAT, which was also paid for by the district and which we started administering in the eighth grade. There is a powerful equity argument for making the tests available, but eighth grade is just ridiculous. The school didn't know how to make a schedule when whole segments were testing in classrooms (we didn't have a common area big enough to hold the testers) while other students were changing classes.

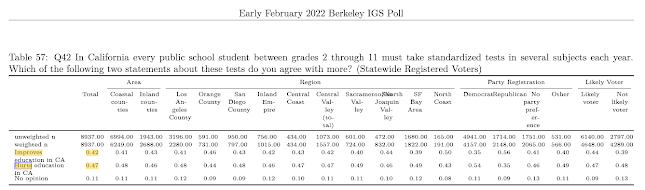

That's just a start. Now come the state-sponsored standardized tests. I know I've posted this chart before, but it illustrates the second semester experience in California schools.

And for dessert, there are extra tests that schools are required to develop in order to practice for the other tests. In a "nice career, be a shame if something happened to it" way, the district offers administrators consultants and materials and programs to help raise test scores. The equation looks something like this:

stagnant test scores + consultants, materials, programs = more practice tests = stagnant test scores - time, resources

And then districts punish schools, their students, teachers, and administrators for "failure" to raise test scores by offering--you guessed it--more consultants, materials, and programs until finally one day, lots of people quit or get fired and the dance begins anew. It's the circle of Life in Schools.

And for what? If the point of all this was to improve instruction, this is certainly not the system we would construct. With state-sponsored standardized tests, there is no opportunity for meaningful analysis by classroom teachers and no comprehensive plan for addressing the issues raised (and I don't mean the predictable default position of "Fuck the teachers, let them figure it out.") However, and this is important, not only is the information produced by these state-sponsored exams effectively useless, the tests do not even measure what they say they measure. They do not show what the profiteers and hucksters and fanatical true-believers say they show.

In an earlier draft of this post I included a lengthy excerpt here from Answer Key talking about reliability and validity, but I don't feel like doing that anymore. As I've been educating myself on this issue--now that I'm no longer consumed by the day-to-day battle for classroom survival--I have discovered how many people have been fighting this fight for years, and it feels like anything I have to say has been said much better than I can, and said over and over.

My latest wake-up call in an ongoing series comes from Dr. Mitchell Robinson, associate professor and chair of music education, and coordinator of the music student teaching program at Michigan State University. And it comes via a paper he wrote in 2014 in which he writes powerfully and eloquently much of what I've been trying to say. A few relevant bits:

Perhaps the most pernicious trend that drives current education reform initiatives is the singular and sole reliance on data as evidence of student learning and teacher effectiveness (Berliner and Biddle 1995).

And, regarding "stack ranking," a system of "dividing employees into arbitrarily predetermined 'effectiveness categories,' based on ratings by managers" (sound familiar?):

The main problem with using stack-ranking systems in teacher evaluation is that the approach is predicated on a series of faulty assumptions. Proponents of this approach believe that:

- teachers are the most important factors influencing student achievement,

- effective teaching can be measured by student test scores and is devoid of context,

- large numbers of American teachers are unqualified, lazy, or simply ineffective, and

- if we can remove these individuals from the work-force, student test scores will improve. (Amrein-Beardsley 2014, 84–88)

The argument is seductively convincing. There is, however, little to no research-based evidence to support any of these assumptions.

Robinson goes on to dispute each one of these assumptions, and I encourage you to read the whole paper, but I do want to include one example, as I don't think I have yet ranted about this specific defect in the current testing/accountability model. On child poverty, from the paper:

Similarly, much of the rhetoric surrounding the so-called “teacher effect” not only ignores the role of poverty in student learning, but actively dismisses this concern.

<snip>

Again, the research here is abundantly clear. When results are controlled for the influences of poverty, nearly every international test of student learning shows that American students score at the top of the rankings. For example, when test scores for U..S students on the 2009 Program for International Assessment (PISA) exams were disaggregated by poverty levels, American children from middle– and upper–socioeconomic status families per-formed as well or better than students from the top three nations in the rankings: Canada, Finland, and South Korea(Walker 2013a).

It occurs to me that I have very little to add to what Dr. Robinson, Diane Ravitch, Peter Greene at Forbes, Bob Shepherd (and here), Jan Resseger, Dennis Shirley, the people at FairTest, and many, many others have said better than I ever could, and they've been saying it for a long time. I want to acknowledge authors whose books I haven't even had time to read yet because I was, you know, teaching--authors such as Alfie Kohn; Anya Kamenetz; Daniel Koretz; Peter Sacks; Harris, Smith, and Harris; David Hursh; and Arlo Kempf, and others who have done the hard work and heavy lifting to make the case against testing in the face of intense opposition. In fact, the argument has been made, and the argument has been won. So what's the trouble?

It's impossible to get someone to understand something

if their paycheck depends on their not understanding it.

The trouble isn't that we don't know. The trouble is that we won't do.

Time for a change. As I continue my education, I'm going to try and shift from ranting about something we all know to talking about what we can do about it. We just got a new boss in LAUSD, and I don't think the best argument is going to be enough. What are some real strategies for putting an end to this madness?

First, however, I do have one other thing to offer: my own experience. Next time I'll do a last post on data and then let it go for a while. I have other stuff to say, after all.

Next time: Data (scores from state-sponsored standardized tests) is bullshit. Part Three, part two