Front Page News?

In a front-page article that smells a lot like finding something to write about, Los Angeles Times education writer Howard Blume reports on public sentiment regarding public education based on a U.C. Berkeley Institute of Governmental Studies poll partially funded by the Times and conducted more than two weeks ago.

From the subhead: "Poll shows decline in trust by parents who say education suffered during the pandemic." Not exactly breaking news.

In a startling combination of "duh, tell us something we don't know" and "wait, I don't think the data mean what you think they mean," Blume goes on to describe the poll as asking "voters to give schools a letter-grade rating from A to F" and then comparing the responses to the same question from 2011! Mark DiCamillo, director of the poll, concedes that "'the impact of COVID has probably contributed to it.'" You think?

A quick Google search of "pandemic impact on schools and education" yields 292,000,000 hits. Now, that's not always an indication, but anyone who has been alive for the last two years has been inundated with reports about the negative impacts of the pandemic on students and schools. Search "covid pandemic education" in Blume's own paper and the L.A. Times coughs up over 280,000 results.

From Blume himself:

- February 10: "New threat to COVID-era education: Black and Latino teachers are leaving the profession."

- January 7: "LAUSD determined to open amid increase in infections; Montebello schools will delay term."

- January 6: "Omicron stresses schools across California to the limit as they fight to stay open."

- January 4: "Omicron wave is inundating California. How to protect yourself and others."

That's just a selection from this year alone. Big hits from times gone by:

- November 2021: "About 44,000 LAUSD students miss first vaccine deadline and risk losing in-person classes."

- October 11, 2021: "Facing major campus disruption and firings, LAUSD extends staff COVID-vaccine deadline."

- July 25, 2021: "Austin Beutner’s tenure as L.A. schools chief marked more by crisis than academic gains."

- On September 7, 2021 The Times Editorial Board weighed in: "Learning loss is real. Stop pretending otherwise."

- From Blume February 2: "Economic segregation in schools has worsened, widening achievement gaps, study says."

- From Mackenzie Mays January 11, 2022: "California schools face funding crisis as student population declines."

Public Education, you really need a new press agent. I haven't even mentioned fake "CRT" outrage and the erasure of history, or the war on LGBTQ+ youth. Book bans? Seriously? It's no wonder "parents have overwhelmingly concluded that the quality of education worsened during the pandemic."

But have they? How might people have reached that conclusion? Blume reports the polling as if it is based solely on parents' experiences with their own schools, ignoring the impact of his own reporting on pubic opinion. Even if the results of the poll were meaningful, the only person who thinks the decline in "trust" is surprising or noteworthy appears to be Blume. Maybe DiCamillo.

And then there's the poll itself. Let's check off the misleading and useless "A to F" grade framing. It obliterates nuance and prevents respondents from differentiating among different functions of their schools--for example "A" for instruction, "F" for safety. Next, notice the crossed out "their" because the poll asks about California public schools, and for the gazillionth time in a row, people rate their local schools more highly than schools in other parts of the universe. Oh, and while we're at it, some of the worst grades for public schools came from parents with their kid in religious, private, or charter schools. Which is surprising. Said no one ever.

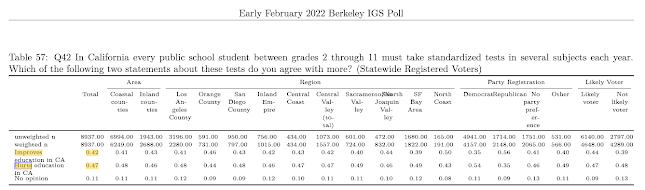

Even though respondents identified as "Black" in the survey rated California schools overall more highly than those identified as "White non-Hispanic," the question of why Black voters are more critical of their local public schools is a really good one and could have been further explored in the survey. It was not. There is a tantalizing little tidbit, though, in the fact that Black voters are "more likely than... voters in other racial or ethnic subgroups to view standardized testing as hurting rather than helping education." Maybe it's because their schools are subjected to a more burdensome testing regime, and they see first-hand the deleterious effects. Just thinking out loud, here.

A word about the "voter" - "parent" conundrum. The poll seems to have included responses from 8937 registered voters and was conducted in English and Spanish online from February 3-10. However, although it does break down some responses according to "Parent of a school-age child," it seems to combine the demographics in its overall statistics. Hence, the significant support actual parents have for their schools is diluted by attitudes more likely formed through interaction with media reports.

For example, if I'm reading Table 1 correctly, and I like to thing that I am, 69% of parents with a child in school rate the school an A, B, or C, while 56% of voters with no child in school do so. That's still a pretty high percentage for people whose sources of information are out of date and/or indirect (i.e. strongly influenced by this kind of reporting), but since the raw data indicate--again, if I'm reading correctly--that 77% of respondents were "not a parent/legal guardian of school-age child," the difference is significant and skews approval downward.

And even more important, if you look carefully, you'll note that the table shows parents whose child is enrolled in an actual "traditional public school," and who therefore presumably know something about it, rate the school at 77% positive (A, B, or C). Yet somehow Blume still concludes that the sky is falling.

The problem with the article is not so much its accuracy as its tone. Instead of comparing "trust" from a survey from over ten years ago, an equally accurate account of the actual, unmediated poll results might read, "Even after two years of crisis, most parents still favor their local schools."

Hint: A "C" is a passing grade. If the "C"s had been included the results wouldn't even look close. That was my conjecture, so I created a chart that does include them, along with the "no opinion"s.

I'm concerned about the eroding public trust we have in our public schools, [Professor Marsh] added.

Voucher proposal advocates hope to capitalize on that discontent.